Anatomy of a Type: Parsons

I suppose that most old typos who have hung up their composing sticks—or are about to—revive in their memories from time to time certain type faces that arouse feelings of nostalgia for a less complicated era of typography.

One type which puts me into that euphoric state is Parsons. And it’s back! Well, like the ubiquitous Cheltenham, it never really disappeared, as it must have survived in a few type cases in out-of-the-way corners of the republic to be cautiously brought out for some “period” bit of fluff such as a business card or a program, or even a personal letterhead.

We might of course ask why in hell shouldn’t Parsons be back, given the numerous resuscitations that have occurred in these days of photographic adaptation prompted by the entrepreneurs of typesetting equipment. If Souvenir was ripe for a new life, and Korrina, not to mention Lining Ronaldson Oldstyle, there’s no reason on earth why Parsons shouldn’t he allowed another little moment in the sun.

But I would have to admit that the man who first fashioned that unique letter would strenuously object to its regeneration. In fact, if anyone has heard a rumbling noise down in Oklahoma, it has been caused by such a protestation.

The designer of Parsons (and he would have been the last to admit it) was a mild-mannered gentleman named Will Ransom (1878–1955) who never sought the limelight but labored all his life in the interest of fine printing.

Ransom was born in Michigan, but he grew up in the state of Washington. Although musically talented, he was apprenticed as a printer and worked in two Washington newspaper offices. During this period he fell under the influence of the art nouveau movement as expressed in the printing of the 1890’s.

Carried away with an enthusiasm for this style, he turned to calligraphy and produced several “limited” editions of his own short stories by hectograph. He also involved himself in wood engraving and bookbinding. In 1901 he made a tentative approach to fine printing, establishing with a friend the Handcraft Press, where he produced two editions in press runs of 100 and 150 copies respectively. Both sold out, and his work received several favorable reviews, including a letter and signed photograph from Elbert Hubbard, the sage of East Aurora, who professed to admire the decoration of the little books.

By 1903 Ransom had saved enough money to finance an art school education. He enrolled in the Chicago Art Institute, where he had the good fortune to meet Fred Goudy, Oz Cooper, and William Dwiggins. Goudy invited him to come out to Park Ridge to help set up a small press in his barn.

This was the beginning of the famed Village Press which Fred and his wife Bertha ran for the rest of their lives. But of course there was not sufficient income from such a tiny venture to keep three people healthy, so when the Goudys decided to remove to Hingham, Mass. in 1904, Ransom remained in Chicago and turned to the more remunerative job of bookkeeper, which he held for nine years. After his marriage in 1911, his wife encouraged him to return to art. When he attempted to establish himself as freelance artist and letterer in Chicago, she helped out by teaching piano.

This turned out to be a successful move for Ransom. He soon had a number of important accounts for his lettering and found time to engage in his first love, the design of books. He became involved with two small publishing ventures—the Brothers of the Book and the Laurentian Publishers.

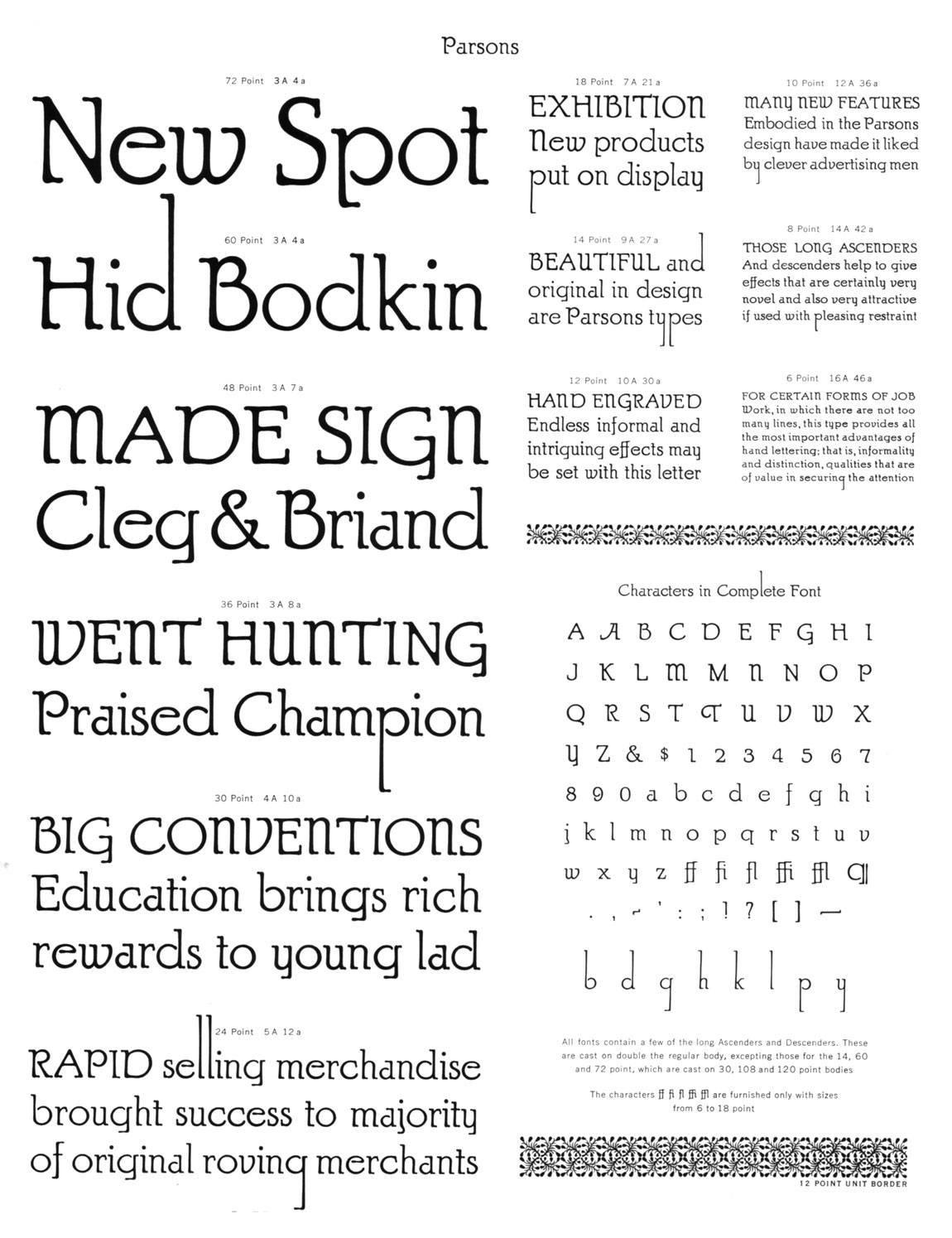

It was with his advertising lettering for the department store Carson Pirie Scott and Co. that Ransom became involved with type design. He had developed a distinctive style of lettering for the Carson ads and the Chicago type foundry Barnhart Brothers & Spindler decided it would make an excellent type. The font was named Parsons after the Carson’s advertising manager. Ransom agreed to supply the drawings, but he was not at all disposed to include the long ascenders and descenders that made the design unique.

In fact, he agreed to supply these characters only if the foundry printed a warning that no more than one was to be used in a single line. In the original design the cap M and N were of lower case form, so when the foundry added normal caps as an option, Ransom was further chagrined.

However, he couldn’t argue with success. Richard N. McArthur, then advertising manager of BB&S, has written that Parsons had a “meteoric success, and when the typos from coast to coast had done their stuff, the typographic landscape appeared, vastly messed up, with a forest of Parsons long letters pointing north and south.”

Ransom was so disillusioned by this experience that he never again attempted to design a type. A set of swash initials designed for the foundry by Sidney Gaunt were produced later, in addition to a set of Parsons Two-Color Initial Decorators. Several of the initials of this font didn’t receive Ransom’s approval.

Later BB&S talked him into a series of borders, brackets and ornaments, along with a set of italic capitals called Clearcut Shaded.

The foundry fully exploited Parsons, producing a boldface version (without Ransom’s help), and a set of exotic border pieces called Parsons Lantern Ornaments.

The descenders and ascenders to which the designer objected were b, d, g, h, k, l, p and y and BB&S did honor Ransom’s request to warn against their overuse. In the great No. 25 specimen book of the foundry a note appeared which stated “Good taste dictates that these decorative characters be used very sparingly—as a general rule not more than one in any line. They should never be doubled, except where the long strokes come close together, as in ll, dl, or yp—not bb, bl or pp—nor one of two different ascenders or descenders occurring together, as bl or py.”

But was anyone listening? A thousand no’s to that! So the promotion of Parsons continued unabated. Possibly the widest use of the type came in its enthusiastic adoption by the moving picture industry for movie titles on the silent screen, which naturally enough shortened the life of the type, although as a novelty face it couldn’t have been expected to endure.

But while it lasted it was a wowzer, and the commercial printers had a wild time with it. It’ll be interesting to see if this current endeavor picks up much steam, but it is doubtful, considering the overabundance of novelty types already available through the photo medium.

If Will Ransom had simply designed Parsons type, he might never have been heard from again, but he went on to become one of the distinguished typographers of this century with most of his reputation stemming from his work as a book designer and writer.

He will long be remembered as the historian of the private press, publishing the most important book in this field in 1929, Private Presses and Their Books, which has not yet been surpassed. In the period 1945–1950 he extended this volume with an additional series called Selective Check Lists of Press Books.

In 1941 he was appointed art editor at Oklahoma University Press, where until he died he produced several hundred distinguished books, many of which were selected for The Fifty Books of the Year exhibitions. This helped to establish the Press as one of the best of all American university presses from the standpoint of the design of its books.

All of the Ransom papers representing a half-century of research into the private press movement were presented to the Newberry Library in Chicago in 1955, making this institution one of the important sources for research in this field.

Ransom’s serene and philosophical approach to his work is probably best expressed in a statement written just a year prior to his death. In answer to a question about what he was doing, he wrote: “As of now I spend forty hours a week at the Press, evenings and weekends on correspondence, and work on the ‘Records,’ a little cello scraping—too many activities for any one to get proper attention. It’s a busy and, on the whole, happy life.”

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the February 1978 issue of Printing Impressions.